Summary

- Despite being thousands of miles apart, Libya and Edo State in southern Nigeria are connected by a centuries-old route for trade and the movement of people. Since the outbreak of conflict in Libya in 2011, it has become a major route for human-smuggling and -trafficking. This research paper traces the movement of people along the route, demonstrating how the abuse against people moving has fuelled the conflict economy in Libya.

- Movement from Edo State is in significant part driven by an overwhelming presence in the state of structural violence,1 which is particularly harmful to people who are economically excluded, and to women and girls.

- The violence people experience escalates along the route to Libya and culminates with people becoming part of an ‘abuse-for-profit’2 system. For women and girls in particular, this interlinked violence may include structural exclusion in Edo State, sexual abuse at the hands of border personnel in Niger, and captivity and forced labour in Libyan detention centres.

- To study this dynamic transnational process, the paper applies a feminist approach of a ‘continuum of violence’. This approach connects different types of violence to show how conflict impacts, and is impacted by, less visible forms of violence, such as societal inequities or violence related to repressive political systems.

- The paper uses a qualitative systems analysis to illustrate how the political, economic and security processes that underpin the movement of people produce a ‘continuum’ that connects Edo State to the Libyan conflict.

- By identifying the causal loops and feedback mechanisms at work in this continuum, policymakers can identify strategic points at which to target interventions. Such an analysis creates new opportunities for international efforts aimed at conflict response. Reducing the level of structural violence in Edo State and the pressures behind human-smuggling and -trafficking could eventually contribute to addressing conflict in Libya.

- To operationalize a policy approach that seeks to disrupt the continuum of violence manifested in the movement of people, four broad policy implications are presented in the concluding chapter:

- First, the use of a wider ‘conflict and violence’ lens – instead of a narrower one focused on ‘border and migration management’ – will help conceptualize the question of the movement of people to Libya in a way that allows for productive responses.

- Second, by expanding the stakeholders, sectors, and violences and deaths considered as part of a conflict, a feminist approach can unlock an expanded policy toolbox to mitigate the violences produced by the transnational movement of people.

- Third, and in keeping with the above, the use of language that is inclusive, and that acknowledges the depth and breadth of exclusion and abuses suffered, is a necessary step towards developing effective solutions. Violence, exploitation and coercion were present in all of the journeys discussed by research participants. In the case of the movement of people to Libya, the violence people experience directly fuels the conflict. More attention to these realities is needed to address how they entrench the conflict economy.

- Finally, policymakers should consider the expansion of safe and legal routes for migration from Edo State as a way of preventing people from becoming a resource to be exploited in the Libyan conflict economy.

01 Introduction

A systems analysis reveals a transnational ‘continuum of violence’ connecting Edo State to Libya’s conflict economy.

Libya has been beset by violent conflict since 2011 when popular uprisings sparked a civil war and led to the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi. Since 2011, two further major bouts of violent conflict occurred, in 2014 and 2019, while sporadic fighting and insecurity have become a defining feature of the post-Gaddafi landscape.

These events in Libya have been closely connected to developments occurring outside the country’s borders, including in Chad, Italy, Niger, Nigeria and Sudan. For this reason, this research paper focuses on the transnational dynamics that have fuelled conflict in Libya. In particular, the paper contends that the feminist approach of the ‘continuum of violence’ provides a productive lens through which to observe and understand the interactions between different forms of violence and conflict across borders.

Continuums of violence can be understood as connecting the ‘violence of everyday life, through the structural violence of economic systems that sustain inequalities and the repressive policing of dictatorial regimes, to the armed conflict of open warfare’ across borders.3 Such an approach shows the connections between eruptions of conflict and instances of violence, often happening across vast geographies, and demonstrates how causes and impacts of conflict are transnational.

To implement this approach, this paper produces a qualitative systems analysis to illustrate how the political, economic and security processes that underpin the movement of people produce a continuum of violence that connects Edo State to the Libyan conflict.

The systems analysis is used to show the connectivity between different types and extents of violence across extensive transnational geographies which together make up the continuum of violence. In particular, it will focus on how violence can cascade across borders to (re)produce violent conflict in Libya.

A systems analysis operates from the premise that conflict is best understood as a social system that contains adaptive structures and evolutionary mechanisms.4 These processes, identified by the qualitative systems analysis, are part of a vast web of social dynamics. For the purposes of this paper, the processes have been simplified as much as possible to allow for an analysis of areas where policy or programmatic interventions may be particularly effective. This analysis focuses on two types of connecting loops: causal loops which identify causal relationships between the key social, political, security and economic factors that shape the interaction between the movement of people and violence; and feedback cycles which show the interplay between the causal loops.

The paper’s approach to analysing conflict settings builds on Ulrike Krause’s work in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Krause identified connections between different experiences of violence, showing how gender-based and sexual violence experienced by both men and women, and carried out by armed groups, was tied to domestic violence in Ugandan refugee settlements.5

Box 1. Categories of violence within a continuum

A ‘continuum of violence’ considers the interconnectivity and causal relationship between structural violence and inequity, direct violence and conflict across geographies.6 Structural violence can be defined as ‘indirect forms of harm exerted by social structures and institutions – enforced on both national and global levels, which carries negative consequences for the health and wellbeing of men and women’.7 This form of violence is less visible, making it hard to quantify, and is often expressed along the lines of inequity, including gendered, racialized and class-based exclusions. And while it impacts a range of metrics, such as quality of life, educational attainment and health, it is also directly related to killings, suicide and conflict.

‘Structural violence, in fact, is by far the most lethal form of violence as well as the most potent cause of other forms of violence.’8 It is connected to direct violence, which is violence inflicted by one person on another, and includes killing, maiming and detention.9 Crucially, structural violence and direct violence co-create each other.10 These interconnections sit along a continuum and can (re)produce violent and armed conflict dynamics.

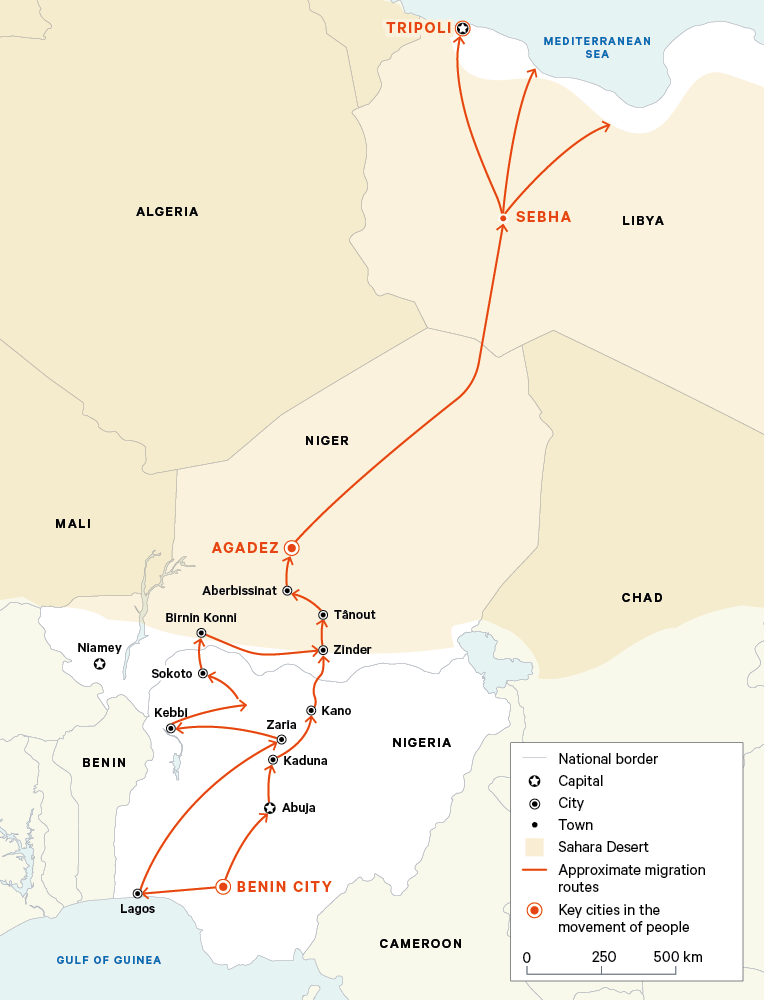

The movement of people from Edo State to Libya

Edo State and Libya have been linked for centuries by a historical route along which people have moved and goods have been traded. The relationship between the two remains significant today, especially with regards to the movement of people. No other sub-Saharan African country has ‘produced more irregular migrants than Nigeria’,11 and Edo State, a small state in southern Nigeria, has accounted for up to 70 per cent of the people moving in certain years.12 The result was that nearly one person in every four households from Benin City, the capital of Edo State, attempted migration in 2017 alone.13

This movement comes in many different forms, but a significant element is related to the trafficking of women and girls. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimated in 2016 that 80 per cent of Nigerian women and girls moving to Europe were trafficked – with almost all of them coming from Edo State.14 The UKAid-funded Stamping out Trafficking in Nigeria (SoTiN) programme reported that 91 per cent of women and 59 per cent of men in their interviews had indicated being trafficked.15

As people start their journey from Edo State, the nature of the violence they experience changes. The closer a person gets to Libya, the more the continuum begins to include substantial levels of direct violence, with people eventually being absorbed by Libya’s conflict economy and becoming part of an ‘abuse-for-profit’ system.

Many of the people moving to Libya have the intention of continuing their travel to Europe. In fact, over the last 10 years, Libya has often been the most prominent departure point for the central Mediterranean route, which sees a high representation of Nigerian people moving. For instance, nearly 40 per cent of people crossing through the central Mediterranean route to Europe in September 2016 were Nigerian. This route is also one of the deadliest. According to IOM’s Missing Migrants project, of the 29,214 people that have been estimated to have gone missing in the last 10 years, 23,032 or 79 per cent of people went missing on the central Mediterranean route.16,17

Many of the journeys start out as ‘attempted migration’. However, the legality, formality, level of agency and motivation to travel, and the extent of exploitation across an entire journey can be hard to determine. The rates of trafficking described above, for example, show that many journeys clearly fall outside traditional policy understandings of migration, not least relevant because the terms ‘migrant’ and ‘migration management’ have taken on specific meanings in the European policy sphere. For these reasons, when broadly describing trends and practices, this paper will use the terms ‘movement of people’ and ‘people moving’, unless the specific nature of a journey (or part thereof) is known.

Box 2. Modes and systems of travel

There are a vast array of routes and approaches to travel. While the figure above outlines a number of routes between Edo State and Libya, via northern Nigeria and Niger, this geography is necessarily an oversimplification of the routes taken by people moving (Figure 1).

Journeys are rarely unidirectional. People may return – from any point along the route – and may travel multiple times, in multiple ways – including by becoming smugglers or traffickers themselves. The journey through Niger and Libya is often also a reflection of multiple payments made along the way, either by people paying in instalments, working at various stages of the journey, or by funds being requested from friends and family in Edo State.18,19

The networks and operations working to smuggle and traffic people to and through Libya are complex and vary in levels of organization and sophistication. More diffuse practices are particularly common for journeys made by men, where the smuggling is organized by ‘a collection of largely independent actors… [In these cases, t]here is no indication of a centralized accounting system (i.e. a ‘kitty’).’20

Two returnees, interviewed in Nigeria, described their travel to Libya in 2023 and discussed the diffuse system that had governed their movement. As one noted:

I messaged [name removed; trafficker] in Benin here and he took me to Lagos. And he said he would meet an agent, that was the process. Each person introduced me to the next contact and that is how I got to Tripoli.21

More ‘elaborate and organised’22 approaches are also common for smuggling and trafficking and, in particular, in the trafficking of women and girls. This more centralized system was also indicated by people living in Edo State.23

About the paper

This research paper is divided into five further chapters. Chapter 2 focuses on Edo State in southern Nigeria, and explores how the people of that state become trapped into the movement of people to Libya. Chapter 3 considers the violence experienced by people moving through Nigeria and Niger, and how that violence increases the closer people are to Libya. Chapter 4 examines how the movement of people is embedded in the Libyan conflict economy and how it fuels the violent conflict in Libya by financing it, manning it24 and providing participants in the conflict for territorial control and authority. Chapter 5 builds on the previous three sections to extrapolate a model of the continuum of violence that connects the Libyan conflict to events in Edo State and vice versa. Finally, Chapter 6 concludes the paper by outlining a feminist and transnational approach to conflict-response policy and programming.

Methodology

The authors adopted a mixed-method approach to research, drawing on both new primary data – in the form of semi-structured interviews and focus groups – and existing secondary data – in the form of policy papers, academic literature and news sources.

Most interviews and focus groups were conducted in three locations in Edo State in August 2023: Benin City, Idogbo and Oza. Benin City is the main urban centre in Edo State and the location from which most journeys start. Idogbo is a suburban location that has particularly high rates of smuggling and trafficking of school-aged teenagers and young adults. Oza is a rural community included for consideration of rural–urban migration and the impact of this movement on agriculture, which is a major economic sector in Edo State. Focus groups and interviews were conducted with a range of participants, including farmers; teachers; businesspeople; community and youth leaders; representatives from non-governmental organizations; law enforcement officials; academics; journalists; a doctor; returnees; and family members of people who have reached Europe or who died on their journey.

Focus group participants and interviewees were identified through a snowballing approach that was mindful of inclusive representation of gender, age, occupation and levels of education. Most of the interviews and focus groups were conducted by two of the paper’s authors, Leah de Haan and Dr Iro Aghedo, often together, and with the support of two local research assistants. This research was carried out in person and primarily in English, with Dr Aghedo translating local languages and dialects in real time when they were used by participants. Focus group meetings were recorded, transcribed and analysed using a structured thematic approach. The discussions focused on experiences with structural violence, with particular attention to variations due to social exclusion, and how these experiences related to the movement of people. Questions did not inquire into the identity of specific individuals involved in the movement of people or the locations from which people were trafficked or smuggled. Most of the data was collected through focus group discussions. Interviews were held with: (i) research participants who were unable to attend a focus group; (ii) specialists or experts with insights on a particular aspect of the research; or (iii) on topics of particular sensitivity.

Semi-structured interviews with 16 Nigerian smugglers based in Libya were carried out with the support of the Mixed Migration Centre between November and December 2018, and provided a background understanding of the topics discussed. Of these, Tim Eaton interviewed three smugglers who felt comfortable to speak directly in a telephone conversation. These interviews were conducted in a more open and less structured format. In most cases, smugglers preferred to engage with the Mixed Migration Centre’s Libya-based staff to answer questions set through an interview guide.

This research paper is one of three publications from the Human Smuggling and Trafficking through East and West Africa to Libya case study investigated by Chatham House for the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme. The case study seeks to understand how the outbreak of violent conflict in Libya has conditioned the movement of people from Nigeria to Libya via Niger between 2011 and 2023. The other two papers in this series focus on human-smuggling and -trafficking through the city of Agadez in Niger, and on the impact of human-smuggling and -trafficking on Libya’s conflict economy.